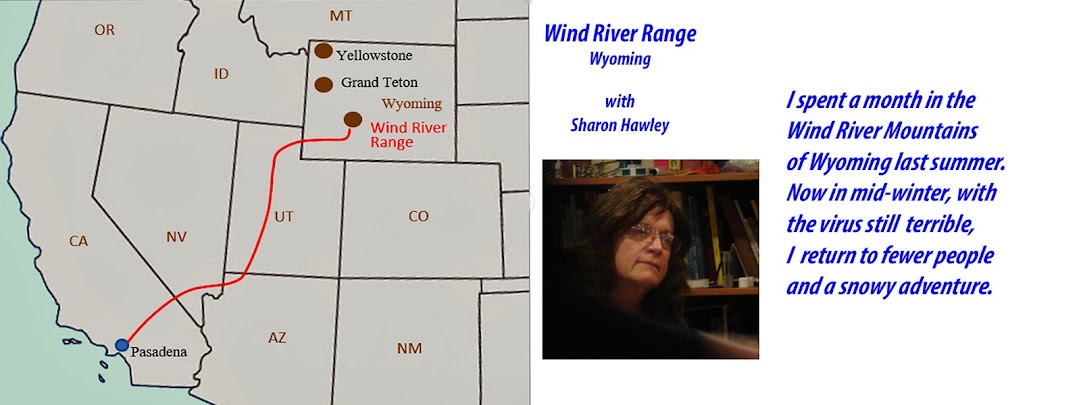

I had a plan for this

trip—escape the pandemic and go to Wyoming where incidence was low, restrictions

almost nil, and where clear air and wilderness awaited a pent-up hiker. After six weeks of solo adventuring, I would

come back to Pasadena when the pandemic would be mostly ended. While gone, I would send inspiring blog

posts, then return, and we would all have fun again. And so it was for five weeks.

I had a plan for this

trip—escape the pandemic and go to Wyoming where incidence was low, restrictions

almost nil, and where clear air and wilderness awaited a pent-up hiker. After six weeks of solo adventuring, I would

come back to Pasadena when the pandemic would be mostly ended. While gone, I would send inspiring blog

posts, then return, and we would all have fun again. And so it was for five weeks.  Starting from a

rabbit hole, in which a long rocky history of this place was explained to me by

geologists, I emerged to the surface experience of seeing, feeling, and contemplating

the Wind River Mountains. I am almost on my way home after millions of

years. I had thought it would be a

beautiful, well planned, moment. But that’s all gone now.

Starting from a

rabbit hole, in which a long rocky history of this place was explained to me by

geologists, I emerged to the surface experience of seeing, feeling, and contemplating

the Wind River Mountains. I am almost on my way home after millions of

years. I had thought it would be a

beautiful, well planned, moment. But that’s all gone now.  |

| I can photoshop out some of the smoke, but the left picture is real |

My plan started well, but the result that

followed was simply wretched—a descending

chain of events not planned for. It isn’t

easy to think of something comforting to say.

They call the eastern Tennessee mountain range “Smoky,” for the haze that

usually envelopes it, but the Wind River Mountains, known for clear, dry, high

elevation air, have changed. It’s not our

smoke (I speak to you Californians) that covers these mountains, it’s

yours. It must be hell there, judging from

the amount of smoke the wind has brought all the way to Wyoming.

My plan started well, but the result that

followed was simply wretched—a descending

chain of events not planned for. It isn’t

easy to think of something comforting to say.

They call the eastern Tennessee mountain range “Smoky,” for the haze that

usually envelopes it, but the Wind River Mountains, known for clear, dry, high

elevation air, have changed. It’s not our

smoke (I speak to you Californians) that covers these mountains, it’s

yours. It must be hell there, judging from

the amount of smoke the wind has brought all the way to Wyoming.  |

| Surprise sunrise on August 21 |

|

| A normal sunrise in Pinedale, Wyoming |

Before sunrise, a thick eerie orange cloud foreboded a sun that rose dark orange. The day and the sun were so dark that at mid-morning I looked directly at the sun without fear of eye injury. As it happened the pandemic in Pasadena was increasing.

A Lake about half a mile away is clearly seen below me, but the lake below it is hazy with smoke.

my tent set up on a

million-dollar lot

to own a lovely lake

a chipmunk came to

visit

a woodpecker thumped

a tree

slid across the lake

on a film of surface

tension

their shadows

on the shallow bottom

in water surface

like Einstein rings

of gravitational

lensing

a leaf of grass

explains

back to where they started

lifted high only for

a time

they crack and break

and may eventually be

buried